Monetary policy refers to the set of actions undertaken by a country’s central bank (or monetary authority) to influence the money supply, interest rates and the broader financial conditions in the economy. The aim is to either stimulate or restrain economic activity in pursuit of the central bank’s mandates (for example, price stability, employment, growth). Typical monetary policy tools include open-market operations (buying / selling government securities), changing the policy interest rate (discount rate or target rate), modifying reserve requirements for banks, and, in more recent times, unconventional measures such as quantitative easing (QE) or forward guidance.

Fiscal policy, on the other hand, is the domain of the national government (its treasury or finance ministry) and involves decisions on government spending (expenditure), taxation (revenues), borrowing and budget balances. Through these levers the government can influence aggregate demand directly, re-distribute resources, and support particular sectors or social objectives.

In short:

monetary policy = central bank + money/credit/interestrate

fiscal policy = government + taxes/spending/borrowing

Core Objectives: What Are the Goals of Each Policy?

Both policy types share broad macro-goals, though each emphasises different transmission channels.

Monetary policy typically pursues:

- Price stability (keeping inflation within a target band)

- Stable economic growth

- Support for full employment (depending on mandate)

- Often stability of the financial system and, indirectly, exchange rate considerations.

Fiscal policy focuses on:

- Stabilising aggregate demand (especially during downturns)

- Influencing the composition of spending and taxes (for growth, equity, redistribution)

- Maintaining sustainable public finances (avoiding unsustainable debt burdens)

- Supporting long-term investment (infrastructure, education, health) and structural change.

Thus, while both tools aim for macro-stability, monetary policy typically acts through financial markets and credit conditions; fiscal policy acts more directly on the “real economy” via spending and taxation.

Key Tools: How Do These Policies Work?

Monetary policy tools include:

- Adjusting the policy interest rate (making borrowing cheaper or more expensive)

- Open market operations: buying/selling government securities to influence bank reserves and money supply

- Reserve requirements: influencing how much banks can lend.

- Forward guidance: signaling future policy path to influence expectations.

- Unconventional tools: quantitative easing, negative rates, asset purchase programmes (especially in crises).

Fiscal policy tools include:

- Government spending: direct expenditure on goods and services, infrastructure, transfers.

- Taxation: changing rates, tax bases, incentives to affect disposable income, investment.

- Borrowing and debt policy: issuing bonds, managing public debt, affecting future obligations and crowding out.

- Automatic stabilisers: built-in fiscal mechanisms that respond automatically to economic cycles (e.g., unemployment benefits).

Both policy types can be deployed in two broad stances:

- Expansionary monetary policy – lowering interest rates, increasing money supply, to stimulate borrowing, spending, investment, and economic growth.

- Contractionary monetary policy – raising interest rates, reducing money supply, to curb inflation, slow overheating.

- Expansionary fiscal policy – increasing government spending and/or cutting taxes, running budget deficits to boost demand.

- Contractionary fiscal policy – reducing government spending and/or increasing taxes (or reducing deficits) typically to cool off demand or preserve fiscal sustainability.

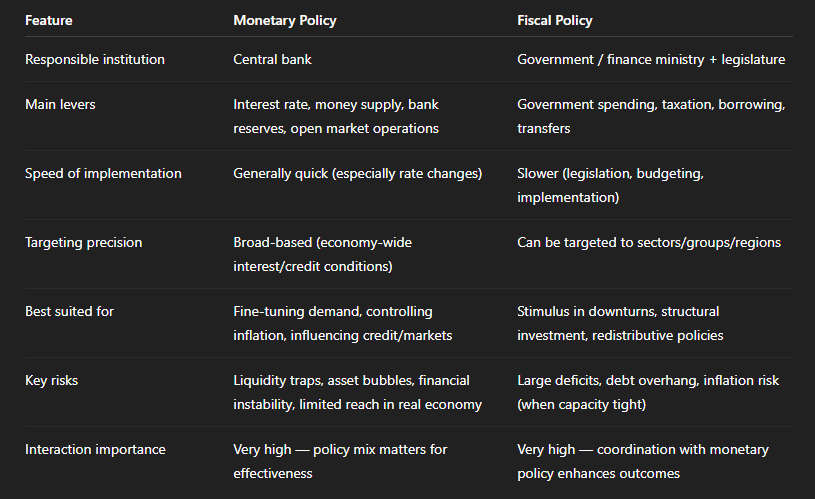

Below are several critical comparative aspects:

- Institutional responsibility: Monetary policy is executed by a central bank; fiscal policy is under the government (treasury/finance ministry + legislature).

- Speed and flexibility: Monetary policy often can be deployed more quickly (interest-rate changes, open market operations). Fiscal policy may suffer longer implementation lags (legislative approval, budgetary planning).

- Transmission mechanism: Monetary policy works via financial markets, credit availability, interest rates; fiscal policy works via direct demand, government purchases, taxation, transfers.

- Precision of targeting: Fiscal policy can be targeted to specific sectors, regions or groups (industry subsidies, income transfers); monetary policy tends to be more broad-based.

- Effect on longer-term structural change: Fiscal policy is better suited to affect the real economy structurally (infrastructure, education) while monetary policy mainly adjusts demand and financial conditions.

- Debt and budget constraints: Fiscal policy is directly tied to government budgets, deficits, and debt dynamics; monetary policy has more flexibility, though extreme actions may raise financial stability issues.

Monetary policy limitations and risks:

- Diminished effectiveness in a liquidity trap (when interest rates are near zero and lowering rates does little).

- Risk of generating asset bubbles if too expansionary for too long.

- Lag between policy implementation and real-economy effects (outside lag). Also risk of mis‐timing.

- Possibly limited in addressing structural real-economy issues (e.g., infrastructure deficiencies, structural unemployment).

- Independence issues: central banks must balance independence with accountability; political pressures may arise.

Fiscal policy limitations and risks:

- Long inside lag — it takes time to decide, legislate and execute fiscal measures.

- Risk of crowding out private investment if heavy borrowing leads to higher interest rates.

- Sustainability concerns: accumulating debt may limit future fiscal space.

- Political economy: fiscal policy decisions may be driven by short-term electoral motives rather than sound long-term macroeconomics.

- Risk of inflation if expansionary fiscal policy is applied when the economy is near full capacity.

The Interaction of Monetary and Fiscal Policy (The Policy Mix)

While each policy can operate in isolation, their interaction — the so-called “policy mix” — matters crucially for macroeconomic outcomes.

Key points of interaction:

- Complementarity: In a downturn, an expansionary fiscal policy (spending increase) combined with accommodative monetary policy (low rates) can provide a stronger stimulus than either alone.

- Conflict / crowding effects: If fiscal policy is too expansionary (large deficits) while monetary policy is trying to fight inflation (raising interest rates), tensions can arise. For example, government spending may fuel inflation while central bank tries to restrain it, reducing effectiveness of both.

- Debt / interest rate spiral: Large fiscal deficits increase government debt. If markets anticipate higher inflation, interest rates may rise, complicating monetary policy.

- Expectations management: Credible monetary policy can anchor inflation expectations, which helps fiscal policy work more effectively; conversely, reckless fiscal policy can undermine monetary credibility.

- Institutional coordination: In some cases, a lack of coordination between government fiscal choices and central bank monetary stance can lead to policy mix problems (e.g., euro-area where multiple sovereign fiscal policies operate under single monetary policy).

Thus, successful macro-management often depends not just on each policy individually, but on how well they are aligned.

Strategic Implications for Market Participants and Policymakers

For policymakers:

- They must recognise the strengths and limitations of each tool and select the right mix given economic conditions (e.g., recession vs inflationary boom).

- Clear communication and credibility are essential — especially for monetary policy, where expectations matter.

- Fiscal policy decisions should take into account long-term sustainability (debt dynamics) and the potential interplay with monetary policy.

- During crises, coordination and rapid response matter; fiscal policy may need to take the lead when monetary policy is constrained (e.g., lower bound on interest rates).

- Institutional design matters: central bank independence and transparent budgetary frameworks support effective policy delivery.

For market participants (investors/traders/etc):

- Interest-rate expectations (monetary policy) strongly impact bond yields, equity valuations, currency moves and risk assets. Monitoring central bank decisions is crucial.

- Fiscal policy changes (tax cuts, government spending packages, deficits) can alter growth prospects, sectoral opportunities (infrastructure, green investments), and credit dynamics.

- The policy mix is especially important: for example, if fiscal stimulus coincides with loose monetary policy, liquidity and growth prospects may expand — but inflation risks go up.

- Conversely, if central bank is tightening but government is running large deficits, risk of interest-rate hikes or inflation surprises increases.

- Structural policy decisions (fiscal) may influence long-term secular trends (infrastructure, demographics, productivity) which traders/investors should account for beyond the short term.

Consider a national economy entering a recession: private demand collapses, unemployment rises, inflation falls or reverses. In this scenario:

- The central bank may cut interest rates (expansionary monetary policy) to reduce borrowing costs and encourage spending/investment.

- The government may launch a stimulus package (higher spending or tax cuts) — expansionary fiscal policy — to boost demand directly.

- If both act together, the downturn may be mitigated more quickly. But if one tool is unavailable (e.g., interest rates already at zero), fiscal policy becomes more critical.

In an inflationary boom: if the economy is at or near full capacity, central bank may raise rates (contractionary monetary policy) to cool inflation. At the same time, government may need to curb spending or raise taxes (contractionary fiscal policy) to help restrain demand; failure to coordinate may undermine efforts.

Moreover, structural shifts such as ageing populations, productivity stagnation or large budget deficits require a long-term fiscal stance (investment in education/infrastructure) and may also require monetary policy to support credit conditions — emphasising the interplay again.

A relevant illustration: In the European monetary union context, the European Central Bank (ECB) sets a single monetary policy for many countries, but each country has its own fiscal policy. The lack of fiscal coordination has sometimes made the ECB’s job much more difficult (for example, excessive government spending in one member state can hamper inflation-control efforts).

Another practical point: Because monetary policy tends to act more rapidly, but fiscal policy has greater direct effect on the real economy, the optimal mix often changes across phases of the business cycle. For instance, when monetary policy is constrained (zero lower bound), fiscal stimulus becomes especially powerful.

Emerging Challenges and Evolving Topics

Several themes are becoming increasingly salient:

- Unconventional monetary policies: When interest rates cannot go lower (zero or negative bound), central banks resort to asset purchases (QE), forward guidance, even yield-curve control. These blur traditional boundaries between monetary and fiscal policy in terms of scale and effect.

- Fiscal-monetary interaction and debt dynamics: The growing size of public debt in many countries raises questions of how monetary policy will cope with large government financing needs without triggering inflation or loss of confidence.

- Distributional effects: Both monetary and fiscal policies can have distributional consequences (who gains, who loses, which asset-owners benefit). For example, expansionary monetary policy may boost asset prices and widen wealth inequality.

- Coordination frameworks: Many economists emphasise that optimal policy outcomes depend on good coordination across monetary and fiscal authorities — the “policy mix” concept is increasingly central.

- Structural and long-term policy: As economies face low growth, demographic change, climate transition, governments may rely more on fiscal policy (public investment) and less on purely cyclical monetary measures. The role of fiscal policy may be rising again after decades of emphasis on monetary policy.

Summary and Key Take-aways

- Monetary policy and fiscal policy are distinct yet complementary macroeconomic tools. Understanding both is essential for navigating economic policy, investing, and financial markets.

- Monetary policy (via central banks) influences funding conditions, credit, interest rates and financial flows; fiscal policy (via government) influences demand, spending, taxation and resource allocation.

- While monetary policy is often more rapid and flexible, fiscal policy can have deeper real-economy effects (especially in downturns or for structural change).

- A well-coordinated policy mix tends to produce better outcomes; mis-alignment can reduce effectiveness or even create conflict (e.g., inflation/fiscal deficit combinations).

- Market participants should monitor both policy sets — interest-rate shifts by central banks and major fiscal policy announcements (tax changes, spending programmes) — as they influence growth, inflation, asset valuations and risk.

- In a changing global environment (high public debt, low growth, climate transition), the relative importance of fiscal policy may be rising again; yet monetary policy remains crucial, especially in managing inflation and financial stability.

- Ultimately, the challenge for policy-makers is to deploy the right tools at the right time, maintain credibility, coordinate across institutions, and adapt to evolving structural conditions.

.png)