Macroeconomic regimes matter. For traders—whether in forex, stocks, commodities or fixed income—the backdrop of the economy strongly influences risk appetite, correlation structures, volatility, and even the most effective strategy frameworks. Terms like “inflation”, “deflation” and “stagflation” are often used in news headlines, but a deep appreciation of what they mean, how they unfold and how markets respond can help elevate trading from purely tactical to strategically informed. This article will first define each regime, then explain their causes and mechanisms, compare their consequences (especially for traders), describe how policymakers respond, and finally provide guidance on what traders should monitor and how they might position accordingly.

Inflation: Definition, Mechanisms and Impacts

Definition: Inflation is the sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over time. In other words, with inflation, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services than before.

Mechanisms & Causes:

There are several pathways through which inflation may arise:

- Demand-pull inflation: where aggregate demand in the economy outpaces aggregate supply (for example, strong consumer spending, investment booms).

- Cost-push inflation: where the cost of production inputs (wages, raw materials, energy) rise, pushing firms to increase prices.

- Built-in inflation (wage-price spiral): expectations of future inflation lead workers to demand higher wages, firms raise prices and so on.

- Monetary factors: excessive money supply growth or ultra-loose monetary policy may contribute by eroding currency value.

Impacts for the economy and markets:

- Purchasing power erodes: a fixed sum of money buys less than before.

- Borrowers (with fixed-rate debt) may benefit, because they repay in devalued currency; savers lose.

- Real interest rates (nominal minus inflation) may become negative, which can encourage spending/investment.

- Asset prices often rise (real estate, commodities, equities with pricing power) as inflation expectations become embedded.

- For traders: inflation often leads to higher volatility, rising yields (in fixed income), currency depreciation (for that country), and possible inflation hedges (commodities, inflation-linked bonds).

Monitoring signals:Traders should watch for accelerating Consumer Price Index (CPI), Producer Price Index (PPI), wage growth statistics, commodity/energy price spikes, and central bank commentary on inflation expectations.

Deflation: Definition, Mechanisms and Impacts

Definition: Deflation is the sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services. It implies negative inflation (i.e., the inflation rate falls below zero).

Mechanisms & Causes:

- Excess supply and weak demand: if goods and services are produced but consumers/revenue are lacking, prices fall.

- Productivity increases: if production efficiency rises dramatically and supply expands or costs fall.

- Contractionary monetary policy: reduction in money supply, credit tightening.

- Debt deflation: high debt burdens lead to reduced spending, demand collapses, triggering price declines.

Impacts for the economy and markets:

- Deferred consumption: if consumers expect prices to fall further, they delay purchases, which suppresses demand and growth.

- Rising real value of debt: borrowers repay with currency that is worth more, meaning debt burdens increase in real terms.

- Liquidity trap potential: interest rates may hit zero yet fail to stimulate spending.

- Asset price deflation: property, equities may collapse.

- For traders: deflationary regimes may favour safe-haven assets, high real yields, stronger currency (in real terms), but overall risk-off sentiment may dominate.

Monitoring signals: Indicators include negative or sharply falling CPI/PPI, weak wage growth, rising unemployment, shrinking GDP, signs of a credit squeeze, collapsing commodity prices.

Stagflation: Definition, Mechanisms and Impacts

Definition: Stagflation is the rare and difficult economic regime in which high inflation coexists with stagnant (or negative) economic growth and elevated unemployment. The term is a portmanteau of “stagnation” and “inflation”. Another way to describe it: the economy is stuck, supply is constrained and prices are rising simultaneously.

Mechanisms & Causes:

- Supply-shock driven: for example a sharp increase in oil or energy prices, raw-material shortages, geopolitical disruption, which raises costs (inflation) and reduces output (stagnation).

- Policy mismanagement: for example, expansive monetary policy in a weak economy produces inflation without growth. Or rigid regulations, structural inefficiencies hamper economic growth while inflation erodes purchasing power.

- De-anchored inflation expectations + structural unemployment: When firms and workers expect high inflation, they act accordingly, but the economy fails to grow, leading to high unemployment.

Why it is so troublesome:

- Traditional policy tools struggle: lowering interest rates to boost growth may worsen inflation; raising rates to curb inflation may deepen stagnation/unemployment.

- It combines “the worst of both worlds” — inflation erodes real incomes; stagnation reduces opportunities; unemployment rises.

- Market behaviour becomes ambiguous: assets that typically hedge inflation may suffer due to weak growth, risk assets may also falter.

Impacts for the economy and markets:

- Cost of living rises while wages stagnate or decline in real terms.

- Corporate margins squeezed from cost pressures and weak demand.

- Investors face difficult tradeoffs: equity earnings under pressure, bonds may offer low real returns, inflation-linked instruments may help but growth is weak.

- For traders: volatility may rise, currency may weaken (especially if local inflation is high), real yields may shoot up, and safe-havens may do well. The environment favours nimble strategies that consider both inflation risks and growth stagnation.

Monitoring signals: Look for simultaneous signs of rising inflation (commodity/energy prices, CPI uptick) + economic slowdown (GDP flat/negative, rising unemployment) + structural issues (supply chains, labour market stress). The 1970s oil shocks are the classic historical example.

Comparative Summary: Inflation vs Deflation vs Stagflation

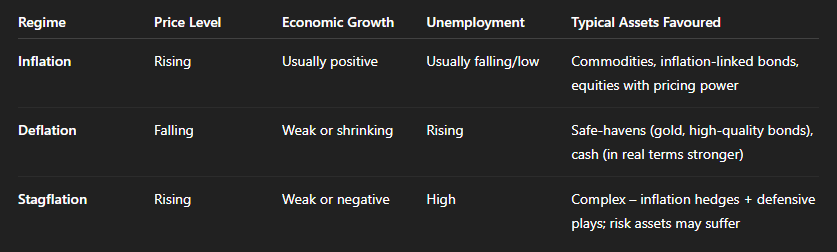

To summarise the key distinctions:

According to one visual guide: in stagflation growth slows, inflation increases, unemployment increases.

Key takeaway: the three regimes are not just academic labels — they imply very different market dynamics and risk profiles. For example, an inflationary environment may encourage higher nominal interest rates, which can hurt fixed-income but help banks; a deflationary environment may push yields toward zero or negative; in stagflation, both growth and prices create conflicting signals.

Implications for Traders and Strategy Considerations

Given the above regimes, what should traders and market participants keep in mind?

1. Asset allocation & positioning:

- In inflation: favour assets with pricing power (companies that can pass on costs), commodities, real assets, inflation-linked bonds, maybe emerging markets with commodity exposure. Focus on sectors like energy, materials.

- In deflation: favour safe-haven assets (government bonds, cash, high-quality sovereigns), sectors that benefit from falling costs or structural growth (technology, certain consumer staples). Beware of long duration risk if deflation turns into a deep recession.

- In stagflation: this is the hardest. You may need a hybrid approach: some inflation hedges (commodities, real assets) but also defensive equities, quality companies, and hedges against growth disappointment. Duration risk may rise; bonds are iffy; real yields may surge. Currency risk is important.

2. Trading environment & risk management:

- Inflationary regimes may generate higher volatility, so traders should guard against inflation surprises and central-bank shock responses (e.g., rapid rate hikes).

- Deflationary regimes may see low yield but higher tail risk (credit stress, liquidity events); risk of “everything falls”. Manage leverage carefully.

- Stagflation creates policy uncertainty: central banks face conflicting imperatives. Trading strategies need to be flexible, monitor policy signals carefully, use hedges and adaptability.

3. Currency & interest‐rate effects:

- Inflation often leads to higher nominal interest rates (to compensate for lost purchasing power) and potentially weaker currency (if inflation runs above peers).

- Deflation can lead to lower or even negative nominal interest rates; currency may strengthen in real terms but weak growth may offset.

- In stagflation: interest rates may rise to combat inflation even as growth lags, causing real yields to rise; currencies with relative inflation/interest spread advantage may perform better.

4. Risk indicators to monitor:

- Inflation measures: CPI, PPI, wage growth, commodity indices, energy prices, inflation expectations (surveys).

- Growth indicators: GDP growth rates, industrial production, retail sales, capacity utilisation, unemployment.

- Supply shocks: oil/energy disruptions, major raw‐material price shocks, supply chain issues.

- Policy statements: central bank minutes, forward guidance, fiscal policy shifts, government debt/deficit levels.

- Market signals: yield curve shape, inflation-linked bond spreads, commodity/futures curves, currency cross‐rates, volatility indices.

5. Scenario planning for traders:

- Suppose inflation accelerates unexpectedly ⇒ central bank may hike rates rapidly ⇒ equity valuations may be challenged, bonds drop, commodity incomes may rise ⇒ shift to inflation hedges.

- Suppose deflation-type shock (e.g., demand collapse) ⇒ central bank cuts rates, seeks stimulus ⇒ risk assets may initially rally but structural collapse may hurt credit assets ⇒ favour safe assets.

- Suppose stagflation scenario emerges ⇒ inflation rises despite sluggish growth ⇒ central bank in policy bind ⇒ high uncertainty, credit spreads widen, volatility spikes ⇒ favour nimble hedging, quality assets, real assets.

Policy Response & Limitations

Monetary/Fiscal policy responses:

- To inflation: central banks typically raise interest rates, tighten monetary policy, reduce money supply growth, raise reserve requirements.

- To deflation: central banks may cut interest rates, pursue quantitative easing, push fiscal stimulus, encourage spending.

- To stagflation: policy becomes very difficult because the standard tools fight one part but may worsen the other. For example, raising interest rates to fight inflation may deepen recession; cutting rates to boost growth may increase inflation.

Limitations and time-lags:

- Policy effects lag: the impact of rate changes or stimulus takes time to transmit.

- Supply shocks may not respond to standard demand-side tools: e.g., energy-price–driven stagflation.

- Inflation expectations: once expectations de-anchor, it becomes harder to control inflation, as wage-price spirals can set in.

Lessons from history:

- The 1970s stagflation era (especially in the US/UK) is illustrative: caused by oil shocks, weak growth & poorly anchored inflation expectations. It forced policymakers to adapt from Keynesian models to monetarist/supply-side thinking.

- Deflationary episodes (e.g., the Great Depression, Japan’s “lost decades”) teach the danger of deferred consumption, credit traps and asset-price collapse.

Case Illustrations for Traders

1. Inflation example:

Imagine an economy where fiscal stimulus is strong, energy prices rise, labour markets tighten and wages start accelerating. The CPI picks up from 2 % to 6 % over 12 months. The central bank signals aggressive rate hikes. In this environment, a commodity trader may benefit from rising oil/gas/metals; a forex trader may look for currency depreciation in the country with high inflation relative to peers; an equities trader may favour companies with strong pricing power.

2. Deflation example:

Conversely, suppose a major systemic shock hits demand (say a pandemic-type event), consumers delay big purchases, unemployment rises, CPI slips into –1 %. The central bank cuts rates to zero, enters quantitative easing. Bond yields drop; high-quality sovereign bonds rally; commodity prices collapse. A trader may shift into safe assets, consider shorting cyclical stocks or commodity producers.

3. Stagflation example:

Consider a period when energy costs shoot up because of supply disruption, inflation moves from 3 % to 8 % in 18 months, yet GDP growth stalls at near-zero and unemployment inches up. The central bank raises rates to fight inflation but growth remains weak. Traders face a dilemma: inflation hedges may help, but growth-sensitive positions suffer. Example: commodity prices may be strong, but industrial companies suffer due to weak demand. Quality bonds get hit by rising real yields. A prudent trader may hedge inflation with some real assets but maintain strong liquidity and defensive positioning.

Strategic Checklist for Traders

Here is a practical checklist traders can use to orient themselves across the three regimes:

- Monitor inflation trend: is CPI/PPI accelerating, flat, or declining?

- Check growth indicators: GDP, industrial production, employment trends.

- Observe supply-side signals: commodity/energy prices, supply chain bottlenecks.

- Watch policy cues: central bank commentary, interest-rate futures, forward guidance.

- Assess market positioning: asset-price trends, yield curve behaviour, credit spreads.

- Adjust asset class exposure: align exposures depending on regime.

- Manage risk: ensure stop-losses, hedges (options, inflation-linked instruments), de-leverage in uncertain regimes.

- Scenario plan: map out inflation-only scenario, deflation-shock scenario, stagflation scenario — and have contingency strategies.

For traders, the macroeconomic regime of inflation, deflation or stagflation is more than a background topic — it is a foundational element that shapes interest‐rates, currency flows, asset prices and risk-reward structures. Recognising which regime the economy is moving toward (or already in) enables more informed strategy and better risk management.

- In inflation, the environment favours pricing power, leverage (carefully), inflation hedges.

- In deflation, the environment favours safety, liquidity, capital preservation rather than aggressive growth bets.

- In stagflation, the environment demands agility, hybrid hedges and caution: you might need inflation protection and defensiveness.

As history attests, shifting regimes often surprise markets (for example the 1970s stagflation or post-2008 deflation worries). Traders who stay alert to regime-change signals and adjust position size, risk and asset class accordingly may enjoy an edge. Ultimately, view inflation/deflation/stagflation as key lenses through which to interpret market dynamics — not as remote academic terms, but as tactical strategic tools.

.png)