In the intricate world of international economics, few concepts are as fundamental yet frequently misunderstood as the Balance of Payments (BOP). Far from being a simple accounting ledger, the BOP is a comprehensive statistical statement that meticulously records all economic transactions between the residents of a country and the rest of the world over a specific period, typically a year. It serves as a vital global scorecard, offering policymakers, investors, and economists a crucial snapshot of a nation's economic health, its competitive position in global trade, and its financial relationship with the international community. The fundamental principle governing the BOP is that it must always balance. This is due to the double-entry bookkeeping system used in its compilation, where every international transaction results in two entries—a credit and a debit—of equal value. In theory, the sum of all accounts should equal zero. In practice, however, statistical discrepancies often arise, but the core identity remains: any deficit or surplus in one part of the BOP must be offset by an equal and opposite entry in another part. This comprehensive guide will demystify the Balance of Payments, breaking down its three primary accounts—the Current Account, the Capital Account, and the Financial Account—and exploring how their balances reveal the underlying strengths and vulnerabilities of a national economy.

The Three Pillars of the Balance of Payments

The Balance of Payments is systematically organized into three main accounts, each capturing a distinct type of international economic activity:

1.The Current Account (CA): Records the flow of goods, services, primary income, and secondary income.

2.The Capital Account (KA): Records capital transfers and the acquisition/disposal of non-produced, non-financial assets.

3.The Financial Account (FA): Records transactions involving financial assets and liabilities.

The Current Account: The Flow of Value

The Current Account is arguably the most closely watched component of the BOP, as it reflects a country's net income from its international transactions. It is composed of four main sub-accounts.

A. Trade in Goods (Visible Trade)

This is the most straightforward component, recording the export and import of physical goods (e.g., cars, oil, machinery).

- Trade Surplus: Exports of goods exceed imports of goods.

- Trade Deficit: Imports of goods exceed exports of goods.

B. Trade in Services (Invisible Trade)

This records the export and import of services (e.g., tourism, transportation, financial services, consulting, intellectual property licensing). As the global economy shifts towards services, this component has become increasingly important for developed nations.

C. Primary Income (Factor Income)

This records income earned from factors of production (labor and capital) owned by residents in foreign countries, and vice versa.

- Credit: Income received by domestic residents from their foreign investments (e.g., dividends, interest, profits) or wages earned abroad.

- Debit: Income paid to foreign residents for their investments in the domestic economy or wages paid to foreign workers.

D. Secondary Income (Current Transfers)

These are one-way transfers of money or goods that do not involve a corresponding economic value in return.

- Credit: Transfers received by domestic residents (e.g., foreign aid, remittances from workers abroad).

- Debit: Transfers paid to foreign residents (e.g., foreign aid given, remittances sent abroad).

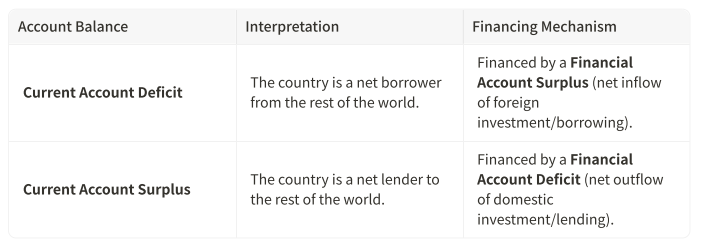

A Current Account Surplus means a country is earning more from the rest of the world than it is spending, making it a net lender to the world. Conversely, a Current Account Deficit means a country is spending more than it is earning, making it a net borrower from the world.

2. The Capital Account: Transfers and Non-Financial Assets

The Capital Account is typically the smallest of the three accounts and focuses on capital transfers and non-produced, non-financial assets.

A. Capital Transfers

These are one-off, non-market transactions that involve the transfer of ownership of an asset or the forgiveness of a liability. Examples include debt forgiveness, inheritance taxes, and transfers of assets by migrants.

B. Acquisition/Disposal of Non-Produced, Non-Financial Assets

This covers transactions involving intangible assets that are not produced, such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and the purchase or sale of land by embassies.

3. The Financial Account: The Flow of Money

The Financial Account records all transactions associated with changes in ownership of the country's international financial assets and liabilities. It is the mechanism through which a Current Account imbalance is financed. The Financial Account is broken down into five main categories:

A. Direct Investment (FDI)

This involves long-term investment where the investor gains a lasting interest and significant influence over the management of an enterprise in another economy. This is often seen as the most stable and beneficial form of financial flow.

- Inward FDI (Credit): Foreign companies investing in the domestic economy.

- Outward FDI (Debit): Domestic companies investing in foreign economies.

B. Portfolio Investment

This involves transactions in equity and debt securities (e.g., stocks and bonds) that do not result in the investor gaining significant influence. It is generally more liquid and volatile than FDI.

C. Other Investment

This is a residual category that includes loans, currency and deposits, and trade credits.

D. Financial Derivatives

This covers transactions in financial instruments whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset.

E. Reserve Assets

These are foreign currency assets held by the central bank (e.g., gold, foreign exchange, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) at the IMF). Changes in reserve assets are used to manage the exchange rate and influence the money supply.

The Fundamental Identity: Why the BOP Must Balance

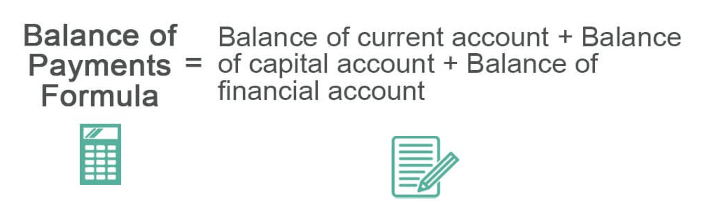

The core accounting identity of the Balance of Payments is expressed as:

This identity is crucial. It means that a country cannot run a Current Account deficit (spending more than it earns) without an equal and opposite surplus in its Capital and Financial Accounts (borrowing or selling assets to finance that spending).

For example, if a country imports more goods and services than it exports (Current Account Deficit), it must finance this excess spending by either borrowing from abroad or selling domestic assets to foreigners, both of which are recorded as a surplus in the Financial Account.

Economic Significance and Policy Implications

The Balance of Payments is more than just an accounting exercise; it is a powerful diagnostic tool for a nation's economic policy and performance.

1. Exchange Rate Stability

The BOP directly influences the supply and demand for a country's currency. A persistent Current Account deficit, for instance, implies a continuous excess supply of the domestic currency (as residents sell it to buy foreign goods and assets), putting downward pressure on the exchange rate. Central banks often use their Reserve Assets (recorded in the Financial Account) to intervene in the foreign exchange market to stabilize the currency.

2. Debt and Sustainability

A prolonged Current Account deficit financed by a Financial Account surplus (borrowing) leads to an accumulation of foreign debt or a net sale of domestic assets. While short-term deficits can be manageable, a persistent deficit raises concerns about the country's long-term ability to service its foreign liabilities, potentially leading to a financial crisis.

3. Trade Policy and Competitiveness

The Trade in Goods and Services component of the Current Account is a direct measure of a country's international competitiveness. A persistent trade deficit can signal underlying issues such as low productivity, high domestic inflation, or an overvalued exchange rate, prompting policymakers to consider trade protectionist measures or structural reforms to boost exports.

4. Investment Climate

The Direct Investment component of the Financial Account is a key indicator of a country's attractiveness to foreign investors. A strong inflow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is generally seen as a positive sign, indicating confidence in the country's long-term economic prospects, stable political environment, and favorable regulatory framework.

Case Study: Interpreting BOP Imbalances

Understanding the context behind a BOP imbalance is critical. Not all deficits are bad, and not all surpluses are good.

The "Bad" Current Account Deficit

A Current Account deficit is often considered problematic if it is driven by excessive consumption (imports of consumer goods) and financed by short-term, volatile capital inflows (e.g., hot money). This scenario, often seen in developing economies, makes the country vulnerable to sudden stops in capital flows, leading to a sharp currency depreciation and economic instability.

The "Good" Current Account Deficit

A Current Account deficit can be beneficial if it is driven by imports of capital goods (machinery, technology) that boost the country's productive capacity and is financed by stable, long-term Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In this case, the borrowing is used to fund investments that will generate future income, allowing the country to service its debt and eventually move into a surplus.

The "Bad" Current Account Surplus

While a surplus (net lending) might seem desirable, a persistent and large surplus can also signal economic issues. It may indicate that the country is under-consuming or under-investing domestically, or that its exchange rate is artificially undervalued, which can lead to trade tensions with deficit countries. For the global economy, large, persistent surpluses and deficits create global imbalances that can contribute to financial instability.

Conclusion

The Balance of Payments is the definitive tool for understanding a nation's economic interaction with the rest of the world. By dissecting the flows of goods, services, income, and financial assets across the Current, Capital, and Financial Accounts, we gain profound insights into a country's financial stability, its trade competitiveness, and the sustainability of its economic policies.In an increasingly interconnected global economy, the BOP is not just an accounting identity; it is a narrative of a nation's economic choices. Whether a country is a net borrower or a net lender, whether it is attracting stable long-term investment or relying on volatile short-term capital, the answers are all meticulously recorded in this essential global scorecard. For anyone seeking to understand the forces that shape global finance and trade, mastering the Balance of Payments is an indispensable first step.

.png)