Capital—whether in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio equity and debt flows, or banking and other short-term flows—has long traversed national borders in search of returns and opportunity. Yet rather than flowing steadily and smoothly, capital tends to surge during favourable global conditions and retract sharply in downturns. These boom-and-bust patterns of cross-border capital flows are intimately connected to what we might call “global economic cycles” or a “global financial cycle.” The scale and speed of these flows have grown as financial markets have deepened and countries have liberalised. For traders and market participants, recognising when the global tide is rising or receding can offer a significant edge. This article will first define what we mean by global economic cycles and capital flows, then explore their drivers, trace their interplay and finally discuss implications for exposure, risk management and policy responses.

Defining Global Economic Cycles and Capital Flow Dynamics

Global Economic Cycles

Global economic cycles refer to co-movements across economies in output, asset prices, credit growth and other macro-financial variables. While standard business cycles are often defined at the national level (expansion, peak, contraction, trough), global cycles span many countries simultaneously and tend to be driven by cross-border interactions—especially financial flows and global risk sentiment.

Economists have identified what is often called the “global financial cycle” (GFCy): periods during which asset prices, leverage, credit, and capital flows move together across the world. Empirical studies show that much of the variation in cross-border capital flows can be linked to global factors—especially global risk aversion—rather than purely domestic fundamentals.

Capital Flows

“Capital flows” is an umbrella term covering various types of cross-border financial movements, including:

- Portfolio equity and debt flows

- Foreign direct investment (FDI)

- Banking flows and other short-term other investment flows

- Reserve and sovereign asset flows

These flows are responsive to interest rate differentials, growth prospects, risk appetite, currency expectations and structural reforms. Over time, the composition of flows evolves: for example, many emerging markets have shifted from debt inflows to equity and “other investment” inflows. Capital flows often exhibit cycles: surges (large inflows), stops (sharp reductions), reversals (net outflows). These are not just random but linked to global cycles. For example, during 2007-2009 and other stressed periods, many emerging markets experienced “sudden stops” in capital flows—sharp reversals with destabilising consequences. Thus, understanding how global economic cycles and capital flow cycles interlink is vital.

The Interplay Between Global Cycles and Capital Flows

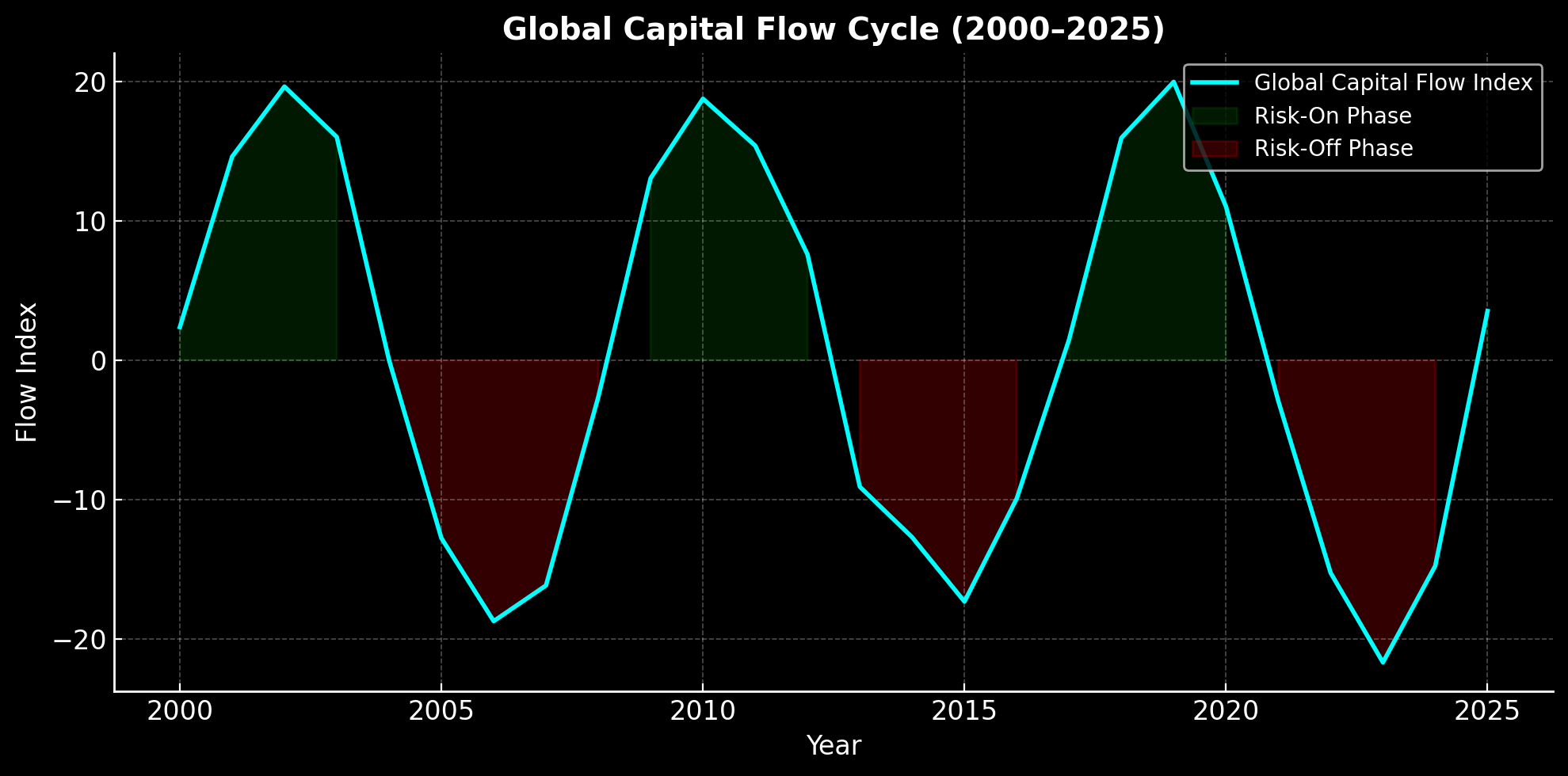

Capital Flow Cycle as a Reflection of Global Risk

Empirical research finds strong correlation between measures of global risk and aggregate gross capital inflows to emerging and advanced economies. One study finds a roughly 75% correlation between a global stock-market-factor and the global capital inflows cycle. When global risk appetite rises (i.e., investors are willing to take more risk), capital flows swell into riskier assets and economies. Conversely, when risk aversion increases (global “risk-off”), flows stop or reverse. Moreover, changes in flows can precede or coincide with turning points in the global cycle.

Structural Drivers: Beyond U.S. Monetary Policy

A common assumption is that U.S. monetary policy (especially the policy rate and quantitative easing) is the primary driver of global flows. While U.S. policy certainly matters, research shows that pure financial shocks (e.g., changes in global risk capacity) may have a larger role. For example, one working paper shows that the global capital flows cycle is strongly linked to a “global risk” measure that captures the co-movement of many economies’ stock returns. Countries with open capital accounts and fixed exchange-rate regimes tend to be more sensitive to global risk shifts.

Composition and Heterogeneity

The effect of global cycles on flows is heterogeneous across countries. For instance, advanced economies and emerging markets respond differently; moreover, within flows, safe asset debt flows and risky equity/FDI flows behave differently in different phases of the cycle. For example, in a downturn of the global financial cycle, countries that are net debtors in safe assets tend to see net outflows of safe assets (i.e., they borrow less or repay more) and a drop in net outflows of risky assets. Thus, not all flow types behave the same. Understanding the composition is key for risk analysis.

Capital Flow Cycles and Economic Boom-Bust Patterns

Historically, capital surges often precede economic expansions in recipient countries, sometimes fuelling credit growth, asset price booms and current-account deficits. When flows reverse, output contracts, investment collapses and crises can follow. In the study covering 1815-2015, patterns of capital flow and commodity cycles were linked to sovereign defaults and crises. Consequently, the global economic cycle (rising phase) tends to coincide with benign risk conditions, capital inflows, rising credit and growth; the downturn phase sees the opposite.

Phases of the Global Cycle and Their Characteristics

Broadly we can characterise three phases of the global economic / capital flow cycle: expansion (boom), peak/turning point, contraction (bust). Of course, reality is more continuous and nuanced, but for analysis this typology helps.

Expansion / Boom Phase

- Global risk appetite is high; investors seek higher returns in riskier assets.

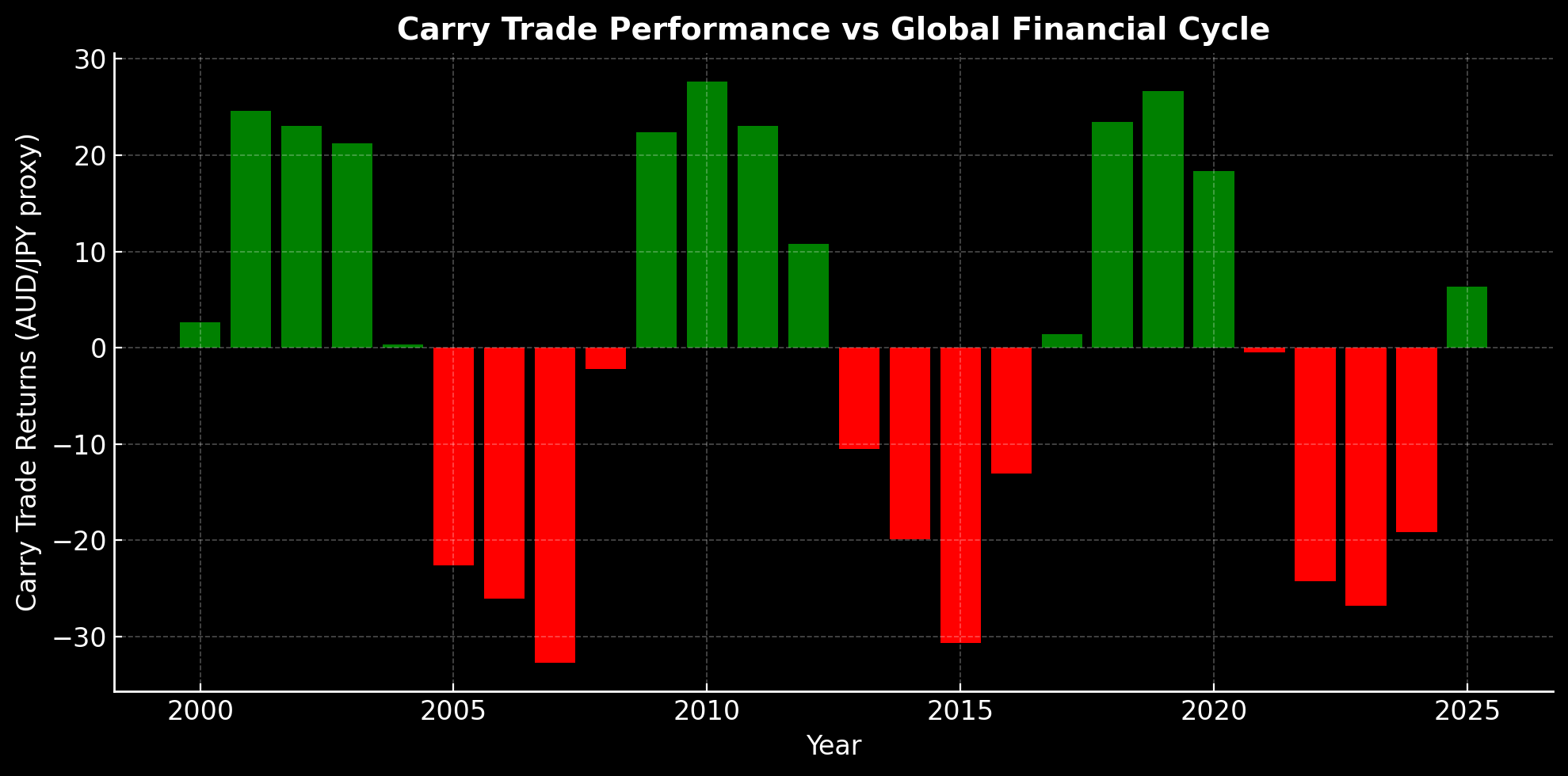

- Interest rates in major economies may be low, encouraging carry trades and search for yield.

- Capital flows surge into emerging markets or sectors offering growth. For recipient economies, credit growth, investment, asset prices and imports tend to rise.

- Macro-financial vulnerabilities accumulate: current account deficits widen, credit growth accelerates, foreign currency borrowing rises.

- The global economy broadly grows; commodity prices often rise.

Peak / Turning Point

- Some combination of higher global risk, tighter monetary policy, rising inflation or external shock triggers a reversal of sentiment.

- Asset prices may topple, carry trades unwind, and global liquidity tightens.

- Capital flow surges slow, stop or reverse.

- In recipient economies, vulnerabilities are exposed. Investment growth declines, credit slows, current account adjustment begins.

- This phase marks the transition to contraction.

Contraction / Bust Phase

- Global risk aversion is elevated; safe-haven flows dominate; risky asset flows are retrenching.

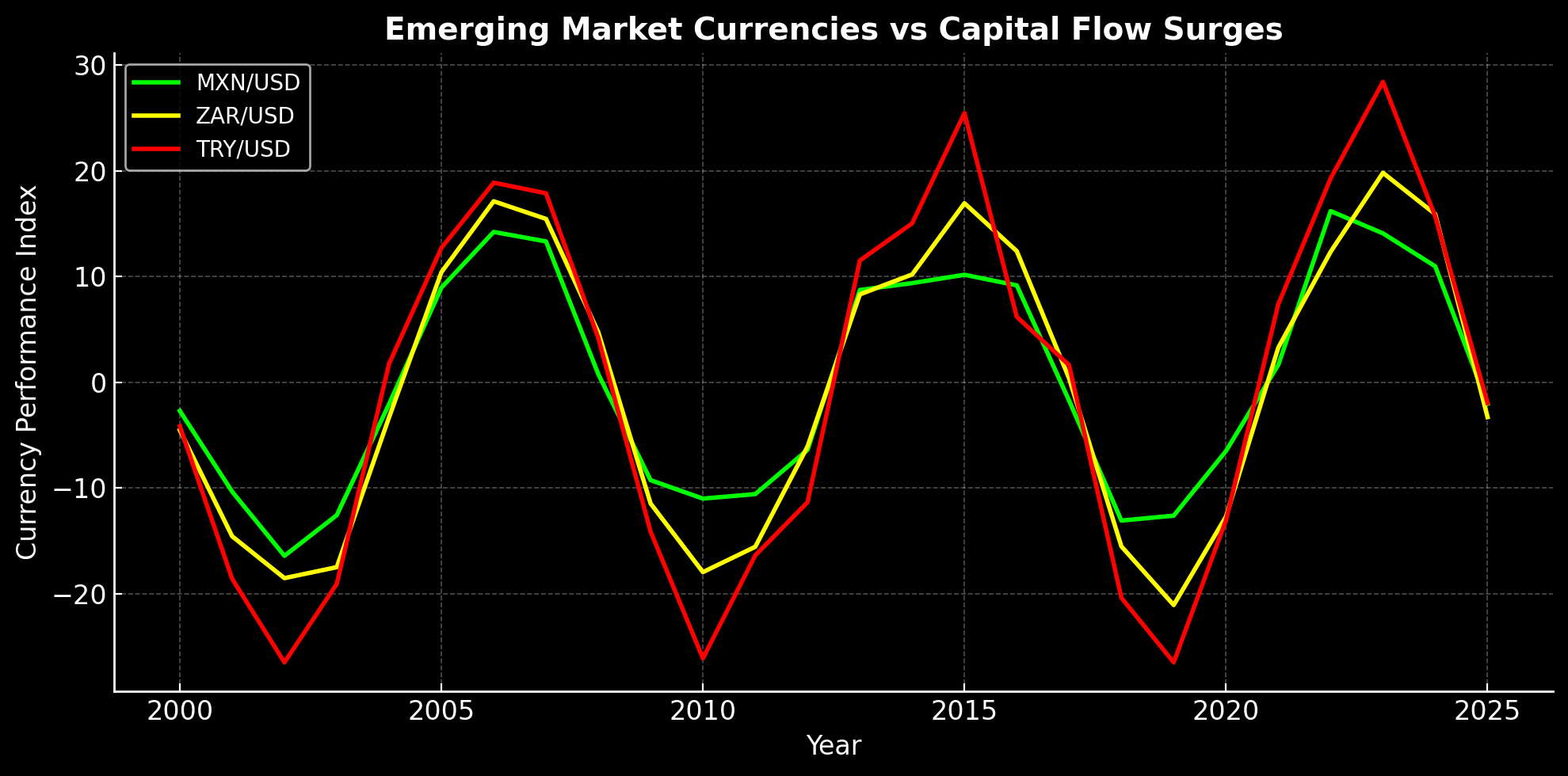

- Emerging markets or highly leveraged economies face sudden stops; capital flight; currency depreciation; loss of reserves.

- Credit contraction, recessionary pressures, reductions in investment, and sometimes sovereign or banking distress.

- The global economy slows; commodity prices often fall; trade slows.

- This phase often triggers policy challenges: FX defence, interest rate hikes, capital controls.

Understanding where we are in the cycle is essential for traders, investors and policymakers alike.

Transmission Channels and Key Drivers

Global Risk and Financial Conditions

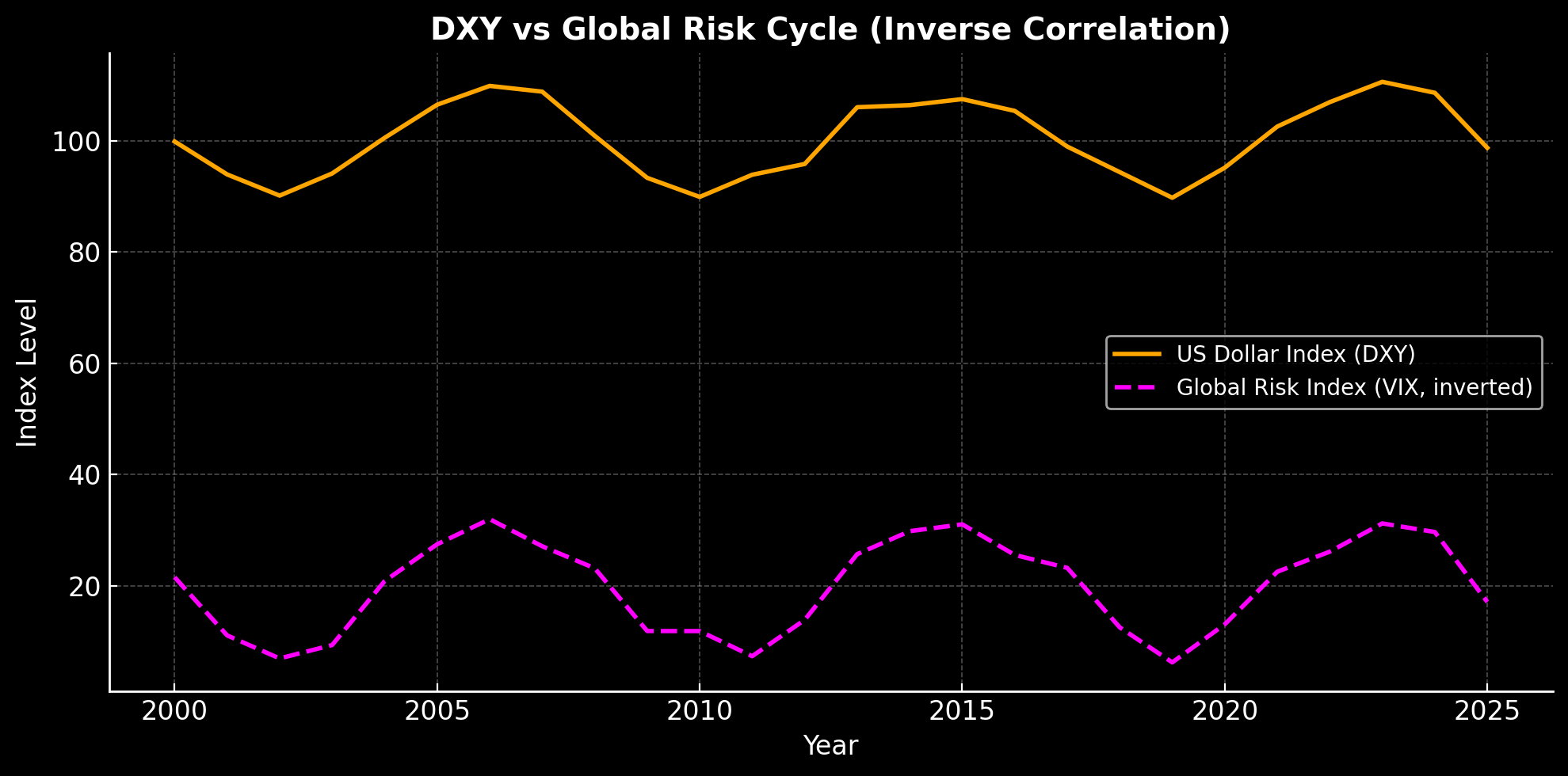

Global risk—often proxied by measures such as the VIX, global stock-market co-movement indexes or “global risk factors”—is a major driver of capital flow cycles. A rise in global risk aversion tends to precede reductions in capital flows.

Monetary Policy and Interest Rate Differentials

Although not the sole driver, monetary policy in large economies (especially the U.S.) matters. Low interest rates encourage search for yield abroad; tightening reversals encourage retrenchment. However, the effect often works through global risk and liquidity rather than purely policy-rate moves.

Structural Drivers: Financial Integration, Capital Account Openness, Exchange-Rate Regimes

Financial liberalisation and deeper integration mean that countries today are more exposed to global cycles. Countries with open capital accounts and pegged exchange-rates tend to be more prone to swings in capital flows driven by global risk.

Composition of Flows and Emerging-Market Vulnerabilities

Short-term flows, banking flows and other investment flows tend to be more volatile and sensitive to risk shifts than foreign direct investment. Emerging markets with high external debt, currency mismatches or weak institutions are particularly vulnerable to reversals.

Commodity Prices and External Terms-of-Trade

Many emerging economies (especially commodity exporters) are exposed to swings in commodity prices. A global upswing raises terms-of-trade, triggers inflows; a downswing reverses it. Capital flows and commodity cycles often move together historically.

Implications for Traders and Investors

Asset Allocation and Risk Management

- Recognising the phase of the global cycle can help inform both regional/country allocation (e.g., emerging vs developed markets) and asset-type allocation (risk assets vs safe assets).

- During the expansion phase, higher yield and risk assets may benefit; during downturns, safe haven assets and sovereign bonds may outperform.

- Monitoring proxies for global risk, capital flows and leverage can provide early warning of shifting tides.

Currency and Carry Trade Risk

- Carry trades (borrowing in low-yield currency to invest in high-yield ones) tend to flourish in risk-on phases and unwind sharply in risk-off phases.

- Traders should quantify the vulnerability to “sudden stops” or reversals: countries with large external debt in foreign currency, large current-account deficits, or pegged exchange-rates are more exposed.

Country/Market Selection

- Emerging markets benefitting from inflows may see strong growth and asset-price appreciation during the boom—but also heightened risk during a reversal.

- Advanced economies may offer more stable returns, or may serve as safe havens in downturns.

- Understanding structural factors (institutions, debt, external sector) is key to assessing resilience.

Timing and Leverage

- It is tempting to chase inflows during the boom—but those are precisely the times when vulnerabilities build.

- Prudence suggests avoiding excessive leverage and avoiding exposure to markets most vulnerable to reversals unless one has clear hedges or exit strategies.

Policy and Macroeconomic Considerations

For policymakers, the interplay between global cycles and capital flows presents a difficult challenge: while openness to capital can foster growth, it creates exposure to global financial conditions beyond domestic control.

Macro-prudential and Capital-Flow Management Tools

Countries can deploy tools such as counter-cyclical capital buffers, foreign-currency debt limits, capital-flow management measures and flexible exchange rate regimes to mitigate the risks from global flow swings. Emerging markets, in particular, may use these tools when exposed to rapid surges or sudden stops of capital.

Exchange-Rate Regime and Monetary Policy Policy Trade-offs

When capital flows are volatile, maintaining a pegged exchange rate plus an open capital account plus monetary independence often becomes impossible (the so‐called “trilemma”). In the context of global financial cycles, this becomes a “dilemma” — domestic monetary policy is constrained by global conditions.

Building Resilience

Reducing external borrowing in foreign currency, accumulating reserves during surges, building sound institutions, and maintaining sustainable current accounts can help economies weather capital-flow reversals. Understanding where the global cycle stands can help policymakers time intervention more effectively.

Case Studies and Historical Evidence

Historical research dating back to the 19th century shows that capital flow surges and reversals often coincide with commodity price swings, credit booms and crises. For example, the study covering 1815-2015 documents how capital flow cycles have accompanied sovereign default episodes. In more recent times, the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and the years afterwards illustrated how tightly interconnected global risk, asset prices, capital flows and output are. Studies show that countries with higher shares of risky assets were more affected when the global cycle turned. Emerging-market episodes of “sudden stop” (sharp reversals of capital inflows) underline the risks associated with boom phases. The literature on “sudden stops” emphasises the role of short‐term flows, currency mismatches and external vulnerability.

Practical Checklist for Traders

For traders and market participants who want to apply the insights from global cycle and capital-flow analysis, consider the following checklist:

- Monitor global risk indicators – measures of investor risk appetite, global asset-price co-movements, volatility, credit spreads.

- Track capital-flow data – especially for emerging markets: gross inflows, outflows, net flows, composition by type.

- Assess country/market vulnerability – external debt levels, foreign‐currency debt, current account deficits/surpluses, institutional strength.

- Gauge monetary and liquidity conditions – in major economies (especially U.S.), as well as carry-trade dynamics (yield differentials).

- Adapt asset allocation to cycle – in risk-on phases, consider emerging markets, commodity exporters, high-yield assets; in risk-off phases, favour safe havens, defensive assets, currencies with reserve status.

- Have exit/hedging strategy – excessive exposure during surges without hedges can lead to outsized losses during reversals.

- Stay mindful of structural breaks – global cycles evolve, and regimes may shift (for example due to geopolitical change, regulatory reforms, or technological shifts).

In today’s globalised financial world, capital flows no longer simply respond to local conditions; they reflect and reinforce global economic cycles. For traders, investors and policymakers, understanding the rhythms of global macro-finance—when capital is surging, when it is reversing, and why—is increasingly critical. Boom phases may bring abundant opportunities, but also build fragilities; bust phases can expose vulnerabilities with speed. By recognising the interplay between global cycles and capital flows, you can better position your strategies: identifying the likely winners in the up-phase, the vulnerable in the down-phase, and importantly, knowing when to shift your stance. Whether you are trading currency pairs, equities, commodities or debt instruments, integrating a global cycle perspective and capital-flow awareness can provide a meaningful strategic edge in navigating complex financial markets.

.png)